How to write a picture book using story grid plot structure

I spent years trying to learn how to structure a plot so that I could become a published children’s picture book author. I read all the story structure books and articles. (There are so many!) I attended workshops and won AMAs with authors. But I never improved enough to catch the attention of literary agents and editors until I started using the Story Grid system.

The problem was all the plotting methods I found were maddeningly vague. Terms like inciting incident and three act structure kept popping up, but with too little explanation of what they actually meant. I tried each plotting method and shared what I wrote with my writing group. Once in a while I stumbled onto a scene or short piece that worked, and I would hear glowing reviews. Mostly though, my peers kindly let me know that my plots were boring and nothing happened in my scenes. All that changed when I found Story Grid. They aren’t paying me. It’s just that I frequently hear other writers echo my own frustrations and wanted to write about what helped me. So if you’re an analytical person like me, or you’re searching for a plotting method with satisfying depth. If you want to consistently write stories that work, read on.

The next section is all about how I found my way to Story Grid, but skip down to

Story Grid Plot Structure for Picture Books for the how-to.

Sign up for my story structure newsletter (no spam, I promise!) to get a high resolution version of this template.

Save the Cat! Leaves Me Hanging

As a child, I dreamed of becoming an author. I spent high school and college taking every writing and literature class available. After graduating with an English degree, I started writing a lot, like good writers apparently do. I shared my writing with my writing group. They tried to be encouraging, but it became clear that after all that education, I did not know how to write a good story. My husband actually said of one of my stories: that is the worst picture book I’ve ever read. (Yes, we’re still married, and he’s a great critique partner!)

Doggedly, I struggled on. I bought every book on writing and story structure that I could find (Save the Cat! and Writing Picture Books and 90 Days to Your Novel), read every article, attended writing workshops, watched tutorial after tutorial. I wrote even more — poems and picture books and longer works, plus two NaNoWriMo novels. That’s 100,000 words! When I was sure I was ready, I paid for a picture book critique session with a big-name editor at an SCBWI conference. In the kindest way possible, she told me my writing was unpublishable.

I Try Writing A Lot But Only Improve A Little

I was so upset, but I wasn’t ready to give up. Convinced I must have missed something, I went back to those books on story structure. I read and reread everything I could find, trying to really understand what published writers meant when they used terms like climax and crisis moment. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much to find that went below the surface. So I turned to my favorite books and started marking them up, trying to sleuth out story structure for myself. Using different colored highlighters, I figured out how much of each chapter was dialogue vs setting vs action.

My writing group teased me, but I spent hours copying my favorite writer’s books, sentence by sentence, trying to teach myself what sentences are actually made of. How do sentences vary in length? How many adjectives are typically included vs nouns and verbs. I learned some things about writing sentences, but also went a little nuts.

My Turning Point

Fortunately, I’m not here to recommend that you go as deep as I did (unless you enjoy that sort of thing). While this close study did improve my line-level writing, my picture books still weren’t good enough to attract the attention of literary agents or editors. Since I was routinely scouring the web for plot structure resources, I discovered the Story Grid podcast shortly after it began in 2016. The podcast was billed as ‘experienced editor teaches struggling writer how to write a book.’ That sounded like just what I needed! Little did I know the rabbit hole I had fallen into.

I spent 2018-19 following the podcast and 2020-22 in the Story Grid Guild, a masters-level course in story structure. Shawn Coyne is the editor who started Story Grid after spending over 25 years as an editor at one of the Big Five publishers. That’s impressive, but the main thing that sets Story Grid apart for me is how comprehensive the system is. I finally learned what the Inciting Incident, Turning Point, Crisis, Climax, and Resolution actually are in excruciating detail. I learned how each one is related to the others and how to reliably execute them again and again. The sweat and tears (there was no blood, thank goodness) spent to get through the SG course was worth it. I started winning contests. Agents and editors started noticing my writing — liking my pitches, requesting to see more, and telling me they loved my stories!

Winning Contests with Story Grid

Story Grid is focused on helping people write full-length novels, especially for adults. I prefer kid lit and found the long form of the novel cumbersome as a learning tool. So I started practicing the Story Grid structure to plot picture book texts — 700 words or less. That’s another great thing about the Story Grid method. It works just as well when applied to the global story arc of a novel, a single scene, and something as short as a flash fiction piece. I’d never written flash fiction before, but after specifically applying what I learned in the Story Grid Guild I was a winner in the Kids’ Choice Kidlit Contest and a WriteMentor Flash Fic Shortlistee ’22.

The best way I can think of to demonstrate how SG works is to go through the five plot structure points using a specific picture book as a demo. (And these five points are just the tip of the iceberg in terms of the analysis tools SG provides.) Below is my plot structure analysis of the picture book Cloudette using Story Grid. Hopefully, Story Grid will click for you like it did for me and help you write a story other people love to read!

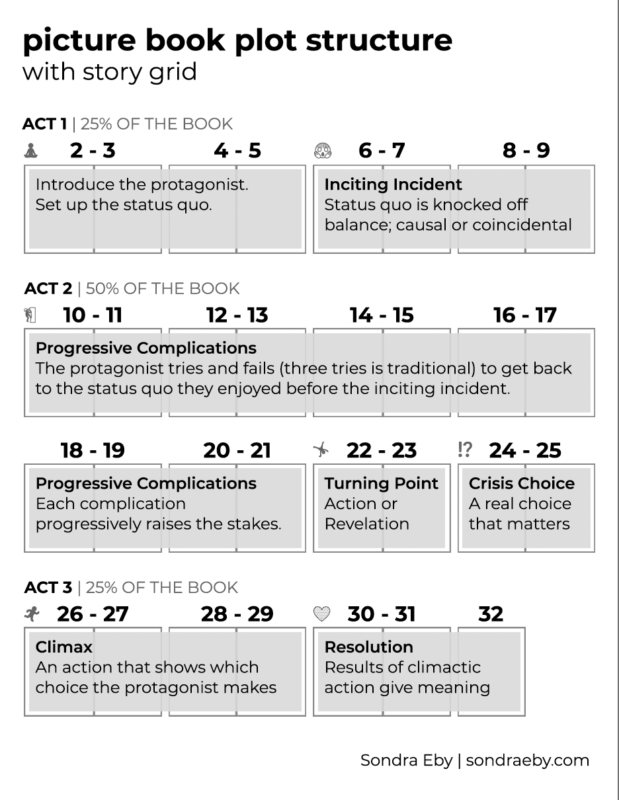

Story Grid Plot Structure for Picture Books

In the Story Grid method, the major plot points for a complete story arc are called the Five Commandments of Storytelling. The commandments are the Inciting Incident, Turning Point Progressive Complication, Crisis, Climax, and Resolution. Many story structure systems use one or more of these terms but don’t go into much detail about what they mean. Story Grid, on the other hand, provides clear definitions and lots of detail about how each of these Five Commandments connects to and builds on the others. Let’s take a close look at Cloudette — a 32 page picture book by Tom Liechtenheld — to understand each commandment.

Inciting Incident

The Inciting Incident is the moment in a story when the status quo of the protagonist’s life is knocked off balance. In a picture book, this moment should happen within the first 9 pages which make up Act 1. In other story structure systems, the inciting incident is sometimes referred to as the story problem.

Inciting Incident – Picture Book Example

But what exactly does “knocked off balance” mean? For Cloudette, the protagonist in our sample picture book, the inciting incident is a revelation that upsets her satisfaction with her own identity as a small cloud. At the beginning of the story, Cloudette is happy to be small; she sees so many advantages. Pages 2-5 describe the status quo of her life. (Page 1 is the cover.) On page 6 though, Cloudette recognizes for the first time that big clouds are doing big, important things. She longs to do big, important things too, but because she is small, she fears she cannot. Suddenly, the comfortable, small places that made her happy are no longer satisfying. Her identity has been knocked off balance. One way or another, she must deal with this new discomfort and try to get back to that sense of being at peace with herself.

Inciting incidents can be causal or coincidental. Either the protagonist did something to cause the incitement or something external happened to the protagonist to upset their life. The incident in Cloudette is coincidental. Cloudette was just fine, until she happened to see big clouds do important things that she wanted to do, but couldn’t.

Complications

Progressive Complications

The second essential structural point in the SG system is the Turning Point Progressive Complication. Before the major turn, though, Act 2 is made of smaller, progressive complications. Essentially, the protagonist tries and fails (three tries is traditional) to get back to the status quo they enjoyed before the inciting incident. The concept of the protagonist trying and failing to solve the story problem is not unique, but Story Grid gets into the nitty gritty of how these progressive complications work.

For instance, every complication needs to be related to the inciting incident. Each complication must make the problem a bit worse than the one before it. By worse, I mean the stakes (or risks) for the protagonist should become increasingly problematic and irreversible. To solve the problem, the protagonist will act the way they did before the inciting incident, but this original strategy will work less and less well. Each failure should result in more and more irreversible choices. The protagonist must keep trying until they have exhausted all their usual tactics and options. They must come to the end of their rope.

Progressive Complication – Picture Book Example

In the example book, when Cloudette realizes that she wants to do big, important things, she goes to her friends in the city where she lives and asks — in her usual helpful way — if they could use her rain at the fire department, the garden center, and the car wash. Three times her friends turn her down. The pictures show Cloudette getting further away from the person she’s talking to and smaller in size — illustrating how each rejection is making Cloudette feel smaller and less important. Her existing friends and her usual friendly helpfulness are failing her.

These complications are directly connected to the inciting incident. Instead of feeling bigger and more important, Cloudette is feeling and looking exactly the opposite. After failing the third time, Cloudette feels so bad about herself that she doesn’t try again. To make matters worse, a terrible storm blows Cloudette out of the city and into the forest where she doesn’t have any friends at all. Cloudette once again tries her usual tactic of being friendly and talking to the residents, but they don’t respond. In Cloudette, all this happens over pages 10-17.

Turning Point Progressive Complication

All these lesser complications lead to the Turning Point Progressive Complication. In a picture book, this moment happens at half to three quarters of the way through Act 2, which typically takes place from page 10 to 25. This could either be an action — something happens to the protagonist — or a revelation — the protagonist learns new information. This major Turning Point is the one that pushes the protagonist to finally respond in a new way.

Turning Point – Picture Book Example

On pages 17 & 18, a frog Cloudette doesn’t know, calls out to her. Instead of responding to the frog with a preconceived notion of how she might help, Cloudette tries something new. She asks the frog what’s going on and listens. In a revelatory turning point, Cloudette learns that the frog’s pond has dried up. Now Cloudette must make an important choice that is directly related to the inciting incident of wanting to do big, important things. That choice is the third commandment in Story Grid.

https://storygrid.com/turning-point-progressive-complication/

Crisis Choice

Many story structures include the essential crisis moment. I personally struggled to understand exactly what the crisis was, though. Is the crisis just the worst thing that happens to the protagonist? Before Story Grid, I might have identified the big storm as the crisis moment. Instead, a crisis is the protagonist’s big choice — either a Best Bad Choice between two terrible options, or a choice between two Irreconcilable Goods where one option is good for the protagonist but bad for others, and the other option is bad for the protagonist but good for others.

In addition to being a choice, the other important thing I learned about how to construct a crisis that hits the reader like a gut punch is that the choice has to really matter to the protagonist, and it has to be a real choice. In other words, a crisis choice that works well would not be something like, should I jump off this cliff or should I run to safety? There is one obviously good option in that example. Instead, a good crisis choice would be more like should I jump off the cliff in front of me or turn and fight the slavering monster behind me? Both of those have meaningful stakes — survival is hanging in the balance. Both of those are very bad options, but the protagonist is being forced to pick one.

Crisis Choice – Picture Book Example

In picture books, the stakes are not typically life and death, but for Cloudette, the crisis choice is extremely meaningful in relation to the inciting incident, the stakes are high, and a decision is unavoidable. Helping the frog who has a dry pond is an opportunity to do something big and important. If she chooses to help the frog and succeeds, she will be happy and at peace with herself once again. But what if she fails again? What will happen to her sense of self? She might feel devastated and give up forever. On the other hand, if she chooses not to help the frog, she won’t risk experiencing crushing failure, but neither will she attain peace of mind. And she’ll be letting down the frog. Who would she be if she didn’t help those in need? Would life even have meaning?

Okay, that may be taking it a bit far for a picture book, but you can see that this is a pivotal developmental moment for Cloudette. If you want the reader to be on the edge of their seat, make sure these stakes are crystal clear. Whichever of the two irreconcilable goods she chooses in this moment will reveal something about Cloudette’s character — who she is inside and who she will be in the world. This crisis choice comes on page 19 in Cloudette, but more typically it would occur on page 24 or 25, right at the end of Act 2.

Climax

The climax launches the story into Act 3, which often happens on pages 26-31 or 32 in a picture book. Like the crisis, the climax appears in other plotting systems but was inadequately defined for me. According to Story Grid, the climax is the action that demonstrates which choice the protagonist makes. If the protagonist turns to fight the monster, that could reveal that they are a fighter. If they jump off the cliff into the water below to avoid the monster, maybe it shows that they will avoid conflict at all cost. Or perhaps they trust their swimming skills more than their fighting skills. What the action reveals about the character of the protagonist depends on what problem the inciting incident set up in the first place.

To feel satisfying to the reader, the climax must pay off the inciting incident. It also needs to happen on the page. It can’t be something that another character reports about the main character. If our example protagonist was just about to fight a monster or jump off a cliff, it would be a huge let down for the next scene to be someone running in to tell the protagonist’s mother that they saw the protagonist fighting. The reader wants to experience the fight!

Climax – Picture Book Example

In a picture book, the climactic actions often happen on pages 26 & 27. In Cloudette, the climax takes a bit longer, happening over pages 20-23, and adds humor to the story. Cloudette tries with all her might to help the frog. She puffs up bigger and bigger, rumbles just a little bit, and finally lets her rain pour down on the dried pond bed. The pond fills up. Though it doesn’t happen the way she thought it would, Cloudette solves the story problem. She does something big and important even though she is small! The moment is hilarious. The illustrations are wonderful. Truly, go read the book to some kids and watch their faces light up.

FYI, if you, like me, have ever had a critique partner or publishing professional tell you that your protagonist needs to demonstrate more agency in solving the story problem — the crisis choice and/or climactic action in your story probably need work.

Resolution

Just as the climax fulfills the promise of the inciting incident, the resolution pays off the climax. Don’t be tempted to skip it just because a picture book has so few pages. The results of the protagonist’s actions provide meaning and help the reader decide whether they want to act like the protagonist in a similar situation or not. Using Story Grid’s method, the resolution is either prescriptive — showing us how to act — or cautionary — showing us how not to act. Most picture books are prescriptive. Brer Rabbit and Peter Rabbit are examples of cautionary tales.

Resolution – Picture Book Example

Tom Liechtenheld doesn’t skimp on the resolution in Cloudette. A typical picture book would resolve over pages 28-31, but the resolution in Cloudette extends from page 24-31. (Page 32 is the back cover.) Cloudette gets all sorts of hilarious and wonderful praise from the many frogs that splash in the pond, her new forest friends, and the “higher ups” who are the big clouds that she wanted to emulate at the beginning of the story. Ever the helpful optimist, Cloudette takes it one step further and decides to go looking for more big and important things a small cloud can do.

Story Grid for Global & Scene Plot Structure

That’s how I use Story Grid to analyze picture books and plot the structure of my own picture books. I use the same structure for middle grade and young adult novels too. Instead of pages each of the Five Commandments of Storytelling happens over many scenes. The ratio of the 3 Acts is the same in a picture book or a longer book, though. Act 1 and Act 3 are roughly half the length of Act 2 no matter the total length of the story. (Another option is to have 4 Acts, and then each of them would be a quarter of the story.) The five plot moments occur at the same points over the course of the book.

These five commandments don’t just happen over the global story arc; they also happen in every scene! Try writing a scene using these five commandments. When I did, my critique partners suddenly stopped asking me what the point of my scene was.

Story Grid System Gets Results

In conclusion, many plot structure systems like Save the Cat! have useful things to offer and will teach you about the three act structure and the inciting incident, but for me, Story Grid is the one that works. It is comprehensive enough that you can teach yourself what you might have otherwise had to pay thousands of dollars to learn getting a master’s degree. It isn’t the quickest system to learn, but it is elegant and versatile once you catch on. Most of all, at least for me, it gets results.

If you have questions about using the Story Grid system to plot picture books, I’d love to nerd out with you! If you think my analysis of Cloudette is off, let’s discuss. There are Story Grid certified editors available to help, if you could use a deeper dive with your specific manuscript. Regardless of the story structure you choose, I wish you all the best and hope you find a system that carries you where you want to go on your writing journey!